All In One Room

by Carl G. Karsch

Just imagine. Robert Smith, General Washington, Napoleon, General & Mrs. Custer, Stanley & Livingstone and hosts of others can be found rubbing shoulders in a single room of Carpenters' Hall. Of course, since that room is the library located on the second floor, notables must stand shoulder-to-shoulder in books. Yet even now they continue to speak volumes. Over two centuries the library has grown from a handful of architectural books to 5,736 titles on a multitude of topics. In fact the library — weighing some 16,000 pounds — has expanded, filling floor to ceiling cabinets in the adjacent hallway. To modern eyes, the collection appears eclectic, perhaps haphazard. In fact, it's a prism reflecting the changing literary tastes of members and their families.

Few early members could afford books on architecture and design. Instead they relied on a collection begun in 1736, the first recorded purchase. Two years earlier, James Portues bequeathed his collection to the Company. Portues landed in Philadelphia as an apprentice on "Welcome," the same ship as William Penn. How quickly the library grew is unknown, since all Company records went up in smoke in November, 1777. Joseph Fox, Company president and ardent Revolutionary, took the records to his country home, believing they would be safe. Unfortunately, the British took revenge on enemies, including Fox, by burning their rural retreats. The library, one of the city's eight specialized libraries, was lucky. During Fox's presidency of 16 years, his home on north 3rd St. was also that of an invaluable workaday book collection for men who erected much of the colonial capital.

With a population of 25,000, Philadelphia was the largest, also the most literate and best read metropolis in the New World. The emerging class of artisans and skilled craftsmen such as the master builders — Franklin called them the "leather aprons" — demanded things to read. And they got them. From 23 print shops poured a torrent of magazines, pamphlets, almanacs and books. Every printer had a shop with domestic and imported titles. In addition, 30 bookshops dotted the city; two had circulating libraries of 700 to 1,000 volumes. European visitors were astounded at the education level of women, the "female booklovers" who patronized them.

Seven weekly newspapers flourished. Each had a circulation of two-to-three thousand, multiplied many times over by copies stocked for patrons at inns, taverns and coffee houses. Franklin's improvements to the postal system hastened news to readers in Boston and Charleston in days, not weeks.

Books crowned the city's reputation as a publishing powerhouse, an honor retained for nearly two centuries. At least 18 important medical works came from local presses before the Revolution. During the same era, the printer who produced many issues of paper currency also printed and bound 36,000 school textbooks. In 1772, ten thousand copies of a new spelling book became available. Three years later appeared a landmark book for the construction industry, the first American edition of Abraham Swan's masterpiece, "The British Architect." More than half the Company's 69 members became "encouragers," pledging one third of the purchase price (50 shillings) before publication to purchase a volume fundamental to their craft. A copy of this rare edition is on the shelves.

The following January (1776) the same printer, Robert Bell, completed an initial run of the nation's first runaway bestseller. His shop on 3rd St. just south of Walnut stood in the shadow of St. Paul's Episcopal Church, built by Robert Smith. Tom Paine's 46-page pamphlet, "Common Sense," challenged not only British authority but the concept of monarchy, in particular King George III. By May, 120,000 copies found their way to every colony. Reprints in newspapers plus copies printed in other cities raised the total to 500,000. Jefferson and John Adams, not known for extravagant praise of others, credited "Common Sense" for expressing in everyday language what most Americans now craved — independence.

Library on the Move

At the urging of George Ingels, elected president in 1795, the library was moved from his home to the Company's meeting rooms on the second floor of New Hall. This two-story structure had been rushed to completion in 1791 to free the original building for rental to agencies of the national government. A freshly minted library committee now began systematic purchases and drew up stringent rules. A member wishing to borrow a book for a week had to sign a note for twice its value. Overdue books cost 12 1/2 cents per day. And the committee accepted returned books only after inspection for possible damage. Fortunately, later committees relaxed the rules.

A catalog of the collection had to wait 28 years, till 1825. Of 110 books, most were on architecture, mechanics or mathematics. The next catalog (1857) totaled 1,464. In the following decade the library expanded by 200%. Titles began to reflect the needs of members' families in an era before public and school libraries. There are shelves devoted to history, geography, poetry, biography and fiction. In one year alone (1885) 68 members of 17 families borrowed 524 books. One avid reader devoured five. A shelf of city directories of the mid to late 19th century acquaints gentlemen visitors with accommodations, restaurants, theaters and other after dark entertainment. More than 50 members published listings and advertisements in the directories' business pages. By century's end, public libraries supplanted those of organizations. In 1900, library purchases ceased; the percentage of books devoted to architecture — the library's original purpose — dropped to .04%.

One More Move

Flooded with new titles, the library must have overflowed its space in New Hall. In 1868 — eleven years after the Company returned to their "old Hall" — members voted to "modernize the committee room [including] inside shutters, walnut bookcases from floor to ceiling extending around the room, new chairs and carpet, proper gas fixtures." The magnificent table and roll top desk came a year later; cost: $295.97. One drawer of the table was set aside for the library committee.

The library is as unique as the Hall itself. Each tells its own story. The building: of construction so precise (and with hand tools) it rivals modern structures. The Library: of voices whose trials and triumphs still instruct us — if we but listen.

A Unique Time Capsule

With its more than 5,700 titles, the Library chronicles reading habits of members and their families for the first 150 years.

Robert Smith, architect of Carpenters' Hall, is one of at least a half-dozen early members who willed some of their most valuable tools — books on architecture — to help create a library. On the opening page of Andrea Palladio's"Architecture" he inscribed his name and purchase date: "Robert Smith his book, Feby. 1754, in Phila." That same year the 32-year-old master builder completed work on the 200-foot steeple of Christ Church, Philadelphia's tallest structure until City Hall, a century and a half later..

One of the most prized volumes, although not on construction, is a rare early copy of the Proceedings of the First and Second Continental Congresses. The small book bears the date September, 1776, two months after the Declaration of Independence. On June 15, 1775, the secretary's unemotional words record a pivotal event: "The Congress then proceeded to the Choice of a General by Ballot, and George Washington Esq., was unanimously elected." Next day he accepted: "...as the Congress desire it, I will enter upon the momentous Duty, and exert every Power I possess in their Service, and for Support of the glorious Cause..."

Napoleon's three-year invasion of Egypt ended in 1801 with his army's surrender to the British. By that time, however, a corps of several hundred artists, scientists and scholars had thoroughly catalogued the Nile's architecture and natural history from Alexandria to the Valley of the Kings. Returning home, they prepared 23 volumes depicting the largely unexplored land with the understated title, "Description De L'Egypt."

The Company purchased this stunning collection in 1840 from Thomas U. Walter, architect of Girard College and the nation's capitol building.

George Catlin, Philadelphia lawyer by profession and self-taught artist by preference, found his calling the morning he encountered a dozen unique visitors — a "delegation of dignified Indians" in full regalia "exactly for the painter's palette." He adds: "Nothing short of the loss of my life shall prevent me from visiting their country and becoming their historian."

He did just that, and more. During the 1830's. Catlin journeyed westward five times, recording in 500 paintings members of 48 tribes, "lending a hand to a dying nation who have no historians or biographers of their own to portray their native looks and history..." Some 400 illustrations engraved from his original paintings fill two compelling volumes with the matter-of-fact title: "Letters and Notes [on] The North American Indians." The Mandan chief, pictured above, was "in splendid costume, trimmed with porcupine quills, ermine fur and long locks of black hair taken from the heads of his enemies he had slain in battle..."

Two years before his death at Little Bighorn (1876), General George Armstrong Custer published what became his eulogy, "My Life on thePlains." He reveals great ambivalence about his assignment to help make possible westward expansion. Custer delights in "lodges of peaceable Indians camped near the fort with their bartering, races, dances, legends, customs and fantastic ceremonies." But he has no illusions on the cruelties — by both sides — in Indian wars. On the book's final page he "bids adieu to civilization" in preparation for an expedition to a "region as yet unseen by human eyes except the Indian." And to a region from which he will not return.

In "Boots and Saddles" Custer's widow (Elizabeth) tells of the perils and privations of frontier Army forts. She closes the book: "On Sunday, June 25th, women gathered together for solace and sang hymns. Our hearts were filled with untold terror. At that very hour the fears of our tortured minds... were reality. The souls of those we thought upon were ascending to meet their maker."

News of Little Bighorn arrived two weeks later.

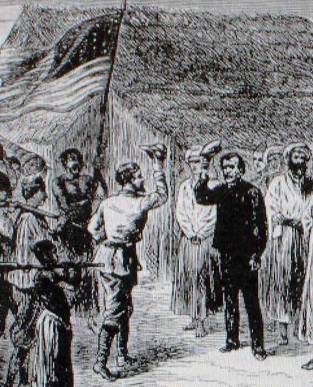

Rarely is a journalist at a loss for words. But on meeting Dr. David Livingstone, famed Scottish explorer and missionary, Henry M. Stanley could only utter: "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" The emaciated, gray-haired man facing Stanley replied, "Yes," lifting his cap slightly.

"How I Found Livingstone" tells the dangerous, first-person adventure leading to this emotionally-charged moment. Livingstone sailed from England in 1864 to discover the Nile river's source in central Africa. Letters ceased after four years. Since then, nothing. Was he dead? Slave traders heard rumors of a white man living on the shore of Lake Tanganyika. Publisher of the New York Herald outfitted a 1000-man expedition, led by Stanley, to find out.

In March, 1871, Stanley's band of porters, guides and hunters left the east African coast. Two-thirds either died or deserted. Stanley carved his epitaph, "Starving H.M.S." on a tree — just in case. After the historic meeting, the two men spent five months planning future exploration. Livingstone remained in Africa where he died in 1873. Stanley, now a best-selling author, sailed to England to serve as a pallbearer at his friend's funeral in Westminster Abbey.